"ECG" redirects here. For other uses, see ECG (disambiguation).

Not to be confused with , Electroencephalography (EEG), Electrooculography (EOG), Electronystagmography (ENG), Polysomnography, or Electromyography (EMG).

| Electrocardiography |

| Intervention |

|

ECG of a heart in normal sinus rhythm.

|

| ICD-9-CM |

89.52 |

| MeSH |

D004562 |

| MedlinePlus |

003868 |

Electrocardiography (ECG or EKG[1] from Greek: kardia, meaning heart[2]) is the process of recording the electrical activity of the heart over a period of time using electrodes placed on a patient's body. These electrodes detect the tiny electrical changes on the skin that arise from the heart muscle depolarizing during each heartbeat.

In a conventional 12 lead ECG, ten electrodes are placed on the patient's limbs and on the surface of the chest. The overall magnitude of the heart's electrical potential is then measured from twelve different angles ("leads") and is recorded over a period of time (usually 10 seconds). In this way, the overall magnitude and direction of the heart's electrical depolarization is captured at each moment throughout the cardiac cycle.[3] The graph of voltage versus time produced by this noninvasive medical procedure is referred to as an electrocardiogram (abbreviated ECG or EKG).

During each heartbeat, a healthy heart will have an orderly progression of depolarization that starts with pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node, spreads out through the atrium, passes through the atrioventricular node and then spreads throughout the ventricles. This orderly pattern of depolarization gives rise to the characteristic ECG tracing. To the trained clinician, an ECG conveys a large amount of information about the structure of the heart and the function of its electrical conduction system.[4] Among other things, an ECG can be used to measure the rate and rhythm of heartbeats, the size and position of the heart chambers, the presence of any damage to the heart's muscle cells or conduction system, the effects of cardiac drugs, and the function of implanted pacemakers.[5]

Contents

- 1 History

- 2 The electrodes and leads

- 2.1 Limb leads

- 2.2 Augmented limb leads

- 2.3 Precordial leads

- 2.4 Specialized leads

- 2.5 Lead locations on an EKG report

- 2.6 Contiguity of leads

- 3 Interpretation of the ECG

- 3.1 Rate and rhythm

- 3.2 Axis

- 3.3 Amplitudes and intervals

- 3.4 Ischemia and infarction

- 3.5 Artifacts

- 4 Medical indications for electrocardiography

- 5 See also

- 6 References

- 7 External links

History

The etymology of the word is derived from the Greek electro, because it is related to electrical activity, kardio, Greek for heart, and graph, a Greek root meaning "to write".

Alexander Muirhead is reported to have attached wires to a feverish patient's wrist to obtain a record of the patient's heartbeat in 1872 at St Bartholomew's Hospital.[6] Another early pioneer was Augustus Waller, of St Mary's Hospital in London.[7] His electrocardiograph machine consisted of a Lippmann capillary electrometer fixed to a projector. The trace from the heartbeat was projected onto a photographic plate that was itself fixed to a toy train. This allowed a heartbeat to be recorded in real time.

An early commercial ECG device (1911)

An initial breakthrough came when Willem Einthoven, working in Leiden, the Netherlands, used the string galvanometer he invented in 1901.[8] This device was much more sensitive than both the capillary electrometer Waller used and the string galvanometer that had been invented separately in 1897 by the French engineer Clément Ader.[9] Einthoven assigned the letters P, Q, R, S, and T to the various deflections,[10] and described the electrocardiographic features of a number of cardiovascular disorders. In 1924, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery.[11]

Though the basic principles of that era are still in use today, many advances in electrocardiography have been made over the years. Instrumentation has evolved from a cumbersome laboratory apparatus to compact electronic systems that often include computerized interpretation of the electrocardiogram.[12]

The electrodes and leads

Proper placement of the limb electrodes. The limb electrodes can be far down on the limbs or close to the hips/shoulders as long as they are placed symmetrically.

[13]

Placement of the precordial electrodes

Ten electrodes are used for a 12-lead ECG. The electrodes usually consist of a conducting gel, embedded in the middle of a self-adhesive pad. The names and correct locations for each electrode are as follows:

| Electrode name |

Electrode placement |

| RA |

On the right arm, avoiding thick muscle. |

| LA |

In the same location where RA was placed, but on the left arm. |

| RL |

On the right leg, lateral calf muscle. |

| LL |

In the same location where RL was placed, but on the left leg. |

| V1 |

In the fourth intercostal space (between ribs 4 and 5) just to the right of the sternum (breastbone). |

| V2 |

In the fourth intercostal space (between ribs 4 and 5) just to the left of the sternum. |

| V3 |

Between leads V2 and V4. |

| V4 |

In the fifth intercostal space (between ribs 5 and 6) in the mid-clavicular line. |

| V5 |

Horizontally even with V4, in the left anterior axillary line. |

| V6 |

Horizontally even with V4 and V5 in the midaxillary line. |

The term "lead" in electrocardiography refers to the 12 different vectors along which the heart's depolarization is measured and recorded. There are a total of six limb leads and augmented limb leads arranged like spokes of a wheel in the coronal plane (vertical) and six precordial leads that lie on the perpendicular transverse plane (horizontal). In medical settings, the term leads is also sometimes used to refer to the ten electrodes themselves, although this is not technically a correct usage of the term.

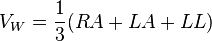

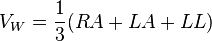

Each of these leads represents the electrical potential difference between two points. For each lead, the positive pole is one of the ten electrodes. In bipolar leads, the negative pole is a different one of the electrodes, while in unipolar leads, the negative pole is a composite pole known as Wilson's central terminal.[14] Wilson's central terminal VW is produced by averaging the measurements from the electrodes RA, LA, and LL to give an average potential across the body:

In a 12-lead ECG, all leads except the limb leads are unipolar (aVR, aVL, aVF, V1, V2, V3, V4, V5, and V6).

Limb leads

The limb leads and augmented limb leads

Leads I, II and III are called the limb leads. The electrodes that form these signals are located on the limbs—one on each arm and one on the left leg.[15][16][17] The limb leads form the points of what is known as Einthoven's triangle.[18]

- Lead I is the voltage between the (positive) left arm (LA) electrode and right arm (RA) electrode:

- Lead II is the voltage between the (positive) left leg (LL) electrode and the right arm (RA) electrode:

- Lead III is the voltage between the (positive) left leg (LL) electrode and the left arm (LA) electrode:

Augmented limb leads

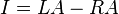

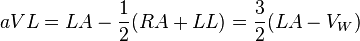

Leads aVR, aVL, and aVF are the augmented limb leads. They are derived from the same three electrodes as leads I, II, and III, but they use Wilson's central terminal as their negative pole.

- Lead augmented vector right (aVR)' has the positive electrode on the right arm. The negative pole is a combination of the left arm electrode and the left leg electrode:

- Lead augmented vector left (aVL) has the positive electrode on the left arm. The negative pole is a combination of the right arm electrode and the left leg electrode:

- Lead augmented vector foot (aVF) has the positive electrode on the left leg. The negative pole is a combination of the right arm electrode and the left arm electrode:

Together with leads I, II, and III, augmented limb leads aVR, aVL, and aVF form the basis of the hexaxial reference system, which is used to calculate the heart's electrical axis in the frontal plane.

Precordial leads

The precordial leads lie in the transverse (horizontal) plane, perpendicular to the other six leads. The six precordial electrodes act as the positive poles for the six corresponding precordial leads: (V1, V2, V3, V4, V5 and V6). Wilson's central terminal is used as the negative pole.

Specialized leads

Additional electrodes may rarely be placed to generate other leads for specific diagnostic purposes. Right sided precordial leads may be used to better study pathology of the right ventricle. Posterior leads may be used to demonstrate the presence of a posterior myocardial infarction. A Lewis lead (requiring an electrode at the right sternal border in the second intercostal space) can be used to study pathological rhythms arising in the right atrium.

An esophogeal lead can be inserted to a part of the tract where the distance to the posterior wall of the left atrium is only approximately 5–6 mm (remaining constant in people of different age and weight).[19] An esophageal lead avails for a more accurate differentiation between certain cardiac arrhythmias, particularly atrial flutter, AV nodal reentrant tachycardia and orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia.[20] It can also evaluate the risk in people with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, as well as terminate supraventricular tachycardia caused by re-entry.[20]

Lead locations on an EKG report

A standard 12-lead ECG report shows a 2.5 second tracing of each of the twelve leads. The tracings are most commonly arranged in a grid of four columns and three rows. the first column is the limb leads (I,II, and III), the second column is the augmented limb leads (aVR, aVL, and aVF), and the last two columns are the precordial leads (V1-V6).

Contiguity of leads

Diagram showing the contiguous leads in the same color

Each of the 12 ECG leads records the electrical activity of the heart from a different angle, and therefore align with different anatomical areas of the heart. Two leads that look at neighboring anatomical areas are said to be contiguous.

| Category |

Leads |

Activity |

| Inferior leads' |

Leads II, III and aVF |

Look at electrical activity from the vantage point of the inferior surface (diaphragmatic surface of heart) |

| Lateral leads |

I, aVL, V5 and V6 |

Look at the electrical activity from the vantage point of the lateral wall of left ventricle |

| Septal leads |

V1 and V2 |

Look at electrical activity from the vantage point of the septal surface of the heart (interventricular septum) |

| Anterior leads |

V3 and V4 |

Look at electrical activity from the vantage point of the anterior wall of the right and left ventricles (Sternocostal surface of heart) |

In addition, any two precordial leads next to one another are considered to be contiguous. For example, though V4 is an anterior lead and V5 is a lateral lead, they are contiguous because they are next to one another.

Interpretation of the ECG

Schematic representation of normal ECG

A typical ECG tracing is a repeating cycle of three electrical entities: a P wave (atrial depolarization), a QRS complex (ventricular depolarization) and a T wave (ventricular repolarization). The EKG is traditionally interpreted methodically in order to not miss any important findings.

Rate and rhythm

A heart rate slower than 60 beats per minute is said to be bradycardic and a rate faster than 100 beats/minute is said to be tachycardic. The heart rate can be approximated quickly by dividing 300 by the number of large boxes between two consecutive QRS complexes on the EKG paper.

The physiologic rhythm of the heart is normal sinus rhythm, wherein the sinoatrial node initiates the cardiac cycle. In normal sinus rhythm a p-wave precedes every QRS complex and the rhythm is generally regular. If this is not the case, the patient may have a cardiac arrhythmia.

Axis

QRS is upright in a lead when its axis is aligned with that lead's vector

The heart's electrical axis is the general direction of the ventricular depolarization wavefront (or mean electrical vector) in the sagittal plane (the plane of the limb leads and augmented limb leads). The QRS axis can be determined by looking for the limb lead or augmented limb lead with the greatest positive amplitude of its R wave. A lead can only detect changes in voltage that are aligned with that lead; therefore the lead that is best aligned with the axis of ventricular depolarization will have the tallest positive QRS complex.

The normal QRS axis is generally down and to the left, following the anatomical orientation of the heart within the chest. An abnormal axis suggests a change in the physical shape and orientation of the heart, or a defect in its conduction system that causes the ventricles to depolarize in an abnormal way.

| Normal |

−30° to 90° |

Normal |

| Left axis deviation |

−30° to −90° |

May indicate left ventricular hypertrophy, left anterior fascicular block, or an old inferior q-wave myocardial infarction |

| Right axis deviation |

+90° to +180° |

May indicate right ventricular hypertrophy, left posterior fascicular block, or an old lateral q-wave myocardial infarction |

| Indeterminate axis |

+180° to −90° |

Rarely seen; considered an 'electrical no-man's land' |

A normal axis can be quickly identified if the QRS complexes in leads I and aVF are both upright. Lead I is positioned at 0° and lead aVF is positioned at 90°. If the QRS is upright in both, its vector of depolarization must be somewhere between these two angles, and is therefore normal axis.

To make it easy to remember, if lead I is negative and lead II is positive so they are facing each other and if we imagine they are hands (we shake hands with the right hand so this is right axis deviation), Alansari Sign.

Amplitudes and intervals

Measuring time and voltage with ECG graph paper

Animation of a normal ECG wave

All of the waves on an EKG tracing and the intervals between them have a predictable time duration, a range of acceptable amplitudes (voltages), and a typical morphology. Any deviation from the normal tracing is potentially pathological and therefore of clinical significance.

For ease of measuring the amplitudes and intervals, an EKG is printed on graph paper at a standard scale: each 1 mm (one small box on the standard EKG paper) represents 40 milliseconds of time on the x-axis, and 0.1 millivolts on the y-axis.

| Feature |

Description |

Pathology |

Duration |

| P wave |

The p-wave represents depolarization of the atria. Atrial depolarization spreads from the SA node towards the AV node, and from the right atrium to the left atrium. |

The p-wave is typically upright in most leads except for aVR; an unusual p-wave axis (inverted in other leads) can indicate an ectopic atrial pacemaker. If the p wave is of unusually long duration, it may represent atrial enlargement. Typically a large right atrium gives a tall, peaked p-wave while a large left atrium gives a two-humped bifid p-wave. |

<80 ms |

| PR interval |

The PR interval is measured from the beginning of the P wave to the beginning of the QRS complex. This interval reflects the time the electrical impulse takes to travel from the sinus node through the AV node. |

A PR interval shorter than 120 ms suggests that the electrical impulse is bypassing the AV node, as in Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome. A PR interval consistently longer than 200 ms diagnoses first degree atrioventricular block. The PR segment (the portion of the tracing after the p-wave and before the QRS complex) is typically completely flat, but may be depressed in pericarditis. |

120 to 200 ms |

| QRS complex |

The QRS complex represents the rapid depolarization of the right and left ventricles. The ventricles have a large muscle mass compared to the atria, so the QRS complex usually has a much larger amplitude than the P-wave. |

If the QRS complex is wide (longer than 120 ms) it suggests disruption of the heart's conduction system, such as in LBBB, RBBB, or ventricular rhythms such as ventricular tachycardia. Metabolic issues such as severe hyperkalemia, or TCA overdose can also widen the QRS complex. An unusually tall QRS complex may represent left ventricular hypertrophy while a very low-amplitude QRS complex may represent a pericardial effusion or infiltrative myocardial disease. |

80 to 100 ms |

| J-point |

The J-point is the point at which the QRS complex finishes and the ST segment begins. |

The J point may be elevated as a normal variant. The appearance of a separate J wave or Osborn wave at the J point is pathognomonic of hypothermia or hypercalcemia.[21] |

|

| ST segment |

The ST segment connects the QRS complex and the T wave; it represents the period when the ventricles are depolarized. |

It is usually isoelectric, but may be depressed or elevated with myocardial infarction or ischemia. ST depression can also be caused by LVH or digoxin. ST elevation can also be caused by pericarditis, Brugada syndrome, or can be a normal variant (J-point elevation). |

|

| T wave |

The T wave represents the repolarization of the ventricles. It is generally upright in all leads except aVR and lead V1. |

Inverted T waves can be a sign of myocardial ischemia, LVH, high intracranial pressure, or metabolic abnormalities. Peaked T waves can be a sign of hyperkalemia or very early myocardial infarction. |

160 ms |

| Corrected QT interval |

The QT interval is measured from the beginning of the QRS complex to the end of the T wave. Acceptable ranges vary with heart rate, so it must be corrected by dividing by the square root of the RR interval. |

A prolonged QTc interval is a risk factor for ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden death. Long QT can arise as a genetic syndrome, or as a side effect of certain medications. An unusually short QTc can be seen in severe hypercalcemia. |

<440 ms |

| U wave |

The U wave is hypothesized to be caused by the repolarization of the interventricular septum. It normally has a low amplitude, and even more often is completely absent. |

If the U wave is very prominent, suspect hypokalemia, hypercalcemia or hyperthyroidism.[22] |

|

Ischemia and infarction

Main article: Electrocardiography in myocardial infarction

Ischemia or non-ST elevation myocardial infarctions may manifest as ST depression or inversion of T waves.

ST elevation myocardial infarctions have different characteristic ECG findings based on the amount of time elapsed since the MI first occurred. The earliest sign is hyperacute T waves, peaked T-waves due to local hyperkalemia in ischemic myocardium. This then progresses over a period of minutes to elevations of the ST segment by at least 1 mm. Over a period of hours, a pathologic Q wave may appear and the T wave will invert. Over a period of days the ST elevation will resolve. Pathologic q waves generally will remain permanently. [23]

The coronary artery that has been occluded can be identified in an ST-elevation myocardial infarction based on the location of ST elevation. The LAD supplies the anterior wall of the heart, and therefore causes ST elevations in anterior leads (V1 and V2). The LCx supplies the lateral aspect of the heart and therefore causes ST elevations in lateral leads (I, aVL and V6). The RCA usually supplies the inferior aspect of the heart, and therefore causes ST elevations in inferior leads (II, III and aVF).

Artifacts

An EKG tracing is affected by patient motion. Some rhythmic motions (such as shivering or tremors) can create the illusion of cardiac dysrhythmia.[24]

Medical indications for electrocardiography

Twelve-lead ECG of a 26-year-old male with an incomplete RBBB

Indications for performing electrocardiography include:

- Suspected myocardial infarction

- Suspected pulmonary embolism

- A third heart sound, fourth heart sound, a cardiac murmur[25] or other findings to suggest structural heart disease

- Perceived cardiac dysrhythmias[25]

- Syncope or collapse[25]

- Seizures[25]

- Monitoring the effects of a cardiac medication

- Assessing severity of electrolyte abnormalities, such as hyperkalemia

The United States Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend electrocardiography for routine screening procedure in patients without symptoms and those at low risk for coronary heart disease.[26][27] This is because an ECG may falsely indicate the existence of a problem, leading to misdiagnosis, the recommendation of invasive procedures, or overtreatment. However, persons employed in certain critical occupations, such as aircraft pilots,[28] may be required to have an ECG as part of their routine health evaluations.

Continuous ECG monitoring is used to monitor critically ill patients, patients undergoing general anesthesia,[25] and patients who have an infrequently occurring cardiac dysrhythmia that would be unlikely be seen on a conventional ten second ECG.

See also

- Electrical conduction system of the heart

- Electrogastrogram

- Electropalatography

- Electroretinography

- Heart rate monitor

References

- ^ Is also known as Electrocardiovascular Gaugometer

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "cardio-". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "ECG- simplified. Aswini Kumar M.D.". LifeHugger. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ Walraven, G. (2011). Basic arrhythmias (7th ed.), pp. 1–11

- ^ Braunwald E. (Editor), Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, Fifth Edition, p. 108, Philadelphia, W.B. Saunders Co., 1997. ISBN 0-7216-5666-8.

- ^ Ronald M. Birse,rev. Patricia E. Knowlden Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004 (Subscription required) – (original source is his biography written by his wife – Elizabeth Muirhead. Alexandernn Muirhead 1848–1920. Oxford, Blackwell: privately printed 1926.)

- ^ Waller AD (1887). "A demonstration on man of electromotive changes accompanying the heart's beat". J Physiol (Lond) 8 (5): 229–34. PMC 1485094. PMID 16991463.

- ^ Rivera-Ruiz M, Cajavilca C, Varon J (29 September 1927). "Einthoven's String Galvanometer: The First Electrocardiograph". Texas Heart Institute journal / from the Texas Heart Institute of St. Luke's Episcopal Hospital, Texas Children's Hospital 35 (2): 174–8. PMC 2435435. PMID 18612490.

- ^ Interwoven W (1901). "Un nouveau galvanometre". Arch Neerl Sc Ex Nat 6: 625.

- ^ Hurst JW (3 November 1998). "Naming of the Waves in the ECG, With a Brief Account of Their Genesis". Circulation 98 (18): 1937–42. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.98.18.1937. PMID 9799216.

- ^ Cooper JK (1986). "Electrocardiography 100 years ago. Origins, pioneers, and contributors". N Engl J Med 315 (7): 461–4. doi:10.1056/NEJM198608143150721. PMID 3526152.

- ^ Mark, Jonathan B. (1998). Atlas of cardiovascular monitoring. New York: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-08891-8.

- ^ RESTING 12-LEAD ECG ELECTRODE PLACEMENT AND ASSOCIATED PROBLEMS.DrTanzil

- ^ "Electrocardiogram Leads". CV Physiology. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Lead Placement". Univ. of Maryland School of Medicine Emergency Medicine Interest Group. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Limb Leads – ECG Lead Placement – Normal Function of the Heart – Cardiology Teaching Package – Practice Learning – Division of Nursing – The University of Nottingham". Nottingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Lesson 1: The Standard 12 Lead ECG". Library.med.utah.edu. Retrieved 15 August 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Electrocardiogram explanation image". Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- ^ Meigas, K; Kaik, J; Anier, A (2008). "Device and methods for performing transesophageal stimulation at reduced pacing current threshold". Estonian Journal of Engineering 57 (2): 154. doi:10.3176/eng.2008.2.05. ISSN 1736-6038.

- ^ a b Pehrson, Steen M.; Blomströ-LUNDQVIST, Carina; Ljungströ, Erik; Blomströ, Per (1994). "Clinical value of transesophageal atrial stimulation and recording in patients with arrhythmia-related symptoms or documented supraventricular tachycardia-correlation to clinical history and invasive studies". Clinical Cardiology 17 (10): 528–534. doi:10.1002/clc.4960171004. ISSN 0160-9289.

- ^ The "Normothermic" Osborn Wave Induced by Severe Hypercalcemia

- ^ Andrew R Houghton; David Gray (27 January 2012). Making Sense of the ECG, Third Edition. Hodder Education. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-4441-6654-5. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP (2000). "Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction". J Am Coll Cardiol 36 (3): 959–69. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. PMID 10987628.

- ^ Segura-Sampedro Juan Jose, Parra-Lopez Loreto, Sampedro-Abascal Consuelo, Muñoz-Rodrıguez Juan Carlos, Atrial Flutter EKG can be useless without the proper electrophysiological basis, International Journal of Cardiology (2014), doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.076

- ^ a b c d e Masters, Jo; Bowden, Carole; Martin, Carole (2003). Textbook of veterinary medical nursing. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 244. ISBN 0-7506-5171-7.

- ^ Moyer VA (2 October 2012). "Screening for coronary heart disease with electrocardiography: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement.". Annals of Internal Medicine 157 (7): 512–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00514. PMID 22847227.

- ^ Consumer Reports; American Academy of Family Physicians; ABIM Foundation (April 2012), "EKGs and exercise stress tests: When you need them for heart disease — and when you don't" (PDF), Choosing Wisely (Consumer Reports), retrieved 14 August 2012

- ^ "Summary of Medical Standards" (PDF). U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

External links

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to ECG. |

- The whole ECG course on 1 A4 paper from ECGpedia, a wiki encyclopedia for a course on interpretation of ECG

- Wave Maven - a large database of practice ECG questions provided by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

- PysioBank - a free scientific database with physiologic signals (here ecg)

|

Emergency medicine · Health science

|

|

| Emergency medicine |

- Emergency department

- Emergency medical services

- Emergency nursing

- Emergency physician

- Emergency psychiatry

- Medical emergency

- Golden hour

- International emergency medicine

- Trauma center

- Triage

- NACA score

- Emergency medicine journals

|

|

| Equipment |

- Bag valve mask (BVM)

- Chest tube

- Defibrillation (AED

- ICD)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG)

- Intraosseous infusion (IO)

- Intravenous therapy (IV)

- Tracheal intubation

- Laryngeal tube

- Combitube

- Nasopharyngeal airway (NPA)

- Oropharyngeal airway (OPA)

- Pocket mask

|

|

| Drugs |

- Atropine

- Amiodarone

- Epinephrine / Adrenaline

- Magnesium sulfate

- Sodium bicarbonate

- Naloxone

|

|

| Organisations |

- Category:Emergency medicine organisations

- International Federation for Emergency Medicine

- American College of Emergency Physicians

- Australasian College for Emergency Medicine

- Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians

- Royal College of Emergency Medicine

- European Society of Emergency Medicine

- Asian Society for Emergency Medicine

|

|

| Courses / Life support |

- Acute Care of at-Risk Newborns (ACoRN)

- Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS)

- Advanced trauma life support (ATLS)

- Basic life support (BLS)

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

- Care of the Critically Ill Surgical Patient (CCrISP)

- First aid

- Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP)

- Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS)

|

|

- Book:Emergency medicine

- Category:Emergency medicine

- Portal:Medicine

|

|

|

Surgery and other procedures involving the heart (ICD-9-CM V3 35–37+89.4+99.6, ICD-10-PCS 02)

|

|

| Surgery and IC |

|

Heart valves

and septa

|

- Valve repair

- Valvulotomy

- Mitral valve repair

- Valvuloplasty

- Valve replacement

- Aortic valve replacement

- Ross procedure

- Percutaneous aortic valve replacement

- Mitral valve replacement

- production of septal defect in heart

- enlargement of existing septal defect

- Atrial septostomy

- Balloon septostomy

- creation of septal defect in heart

- Blalock–Hanlon procedure

- shunt from heart chamber to blood vessel

- atrium to pulmonary artery

- Fontan procedure

- left ventricle to aorta

- Rastelli procedure

- right ventricle to pulmonary artery

- Sano shunt

- compound procedures

- for transposition of great vessels

- Jatene procedure

- Mustard procedure

- for univentricular defect

- Norwood procedure

- Kawashima procedure

- shunt from blood vessel to blood vessel

- systemic circulation to pulmonary artery shunt

- Blalock–Taussig shunt

- SVC to the right PA

- Glenn procedure

|

|

|

Cardiac vessels

|

- CHD

- Angioplasty

- Bypass/Coronary artery bypass

- MIDCAB

- Off-pump CAB

- TECAB

- Coronary stent

- Bare-metal stent

- Drug-eluting stent

- Bentall procedure

- Valve-sparing aortic root replacement

|

|

|

Other

|

- Pericardium

- Pericardiocentesis

- Pericardial window

- Pericardiectomy

- Myocardium

- Cardiomyoplasty

- Dor procedure

- Septal myectomy

- Ventricular reduction

- Alcohol septal ablation

- Conduction system

- Maze procedure

- Cox maze and minimaze

- Catheter ablation

- Cryoablation

- Radiofrequency ablation

- Pacemaker insertion

- Left atrial appendage occlusion

- Cardiotomy

- Heart transplantation

|

|

|

Diagnostic

tests and

procedures |

- Electrophysiology

- Electrocardiography

- Vectorcardiography

- Holter monitor

- Implantable loop recorder

- Cardiac stress test

- Bruce protocol

- Electrophysiology study

- Cardiac imaging

- Angiocardiography

- Echocardiography

- TTE

- TEE

- Myocardial perfusion imaging

- Cardiovascular MRI

- Ventriculography

- Radionuclide ventriculography

- Cardiac catheterization/Coronary catheterization

- Cardiac CT

- Cardiac PET

- sound

- Phonocardiogram

|

|

| Function tests |

- Impedance cardiography

- Ballistocardiography

- Cardiotocography

|

|

| Pacing |

- Cardioversion

- Transcutaneous pacing

|

|

|

Index of the heart

|

|

| Description |

- Anatomy

- Physiology

- Development

|

|

| Disease |

- Injury

- Congenital

- Neoplasms and cancer

- Other

- Symptoms and signs

- Blood tests

|

|

| Treatment |

- Procedures

- Drugs

- glycosides

- other stimulants

- antiarrhythmics

- vasodilators

|

|

|

|

Medical test: Electrodiagnosis

|

|

| Electrocardiography |

- Vectorcardiography

- Magnetocardiography

|

|

| Central nervous system |

- Electroencephalography (Intracranial EEG)

- Magnetoencephalography

|

|

| Peripheral nervous system |

- Electromyography (Facial electromyography)

- Nerve conduction study

|

|

| Eyes |

- Electronystagmography

- Electrooculography

- Electroretinography

|

|

| Digestive system |

- Electrogastrogram

- Magnetogastrography

|

|

English, GermanEine 10-jährige männlich-kastrierte Kurzhaarkatze wurde wegen einer asymptomatischen Tachykardie vorgestellt, die erstmalig vor zwei Wochen diagnostiziert worden war. Bei der elektrokardiographischen Untersuchung wurde ein normaler Sinusrhythmus mit atrialen Extraystolen und Perioden von paroxysmaler supraventrikulärer Tachykardie mit einer Herzfrequenz von 300 bis 400 min–1 festgestellt. Die echokardiographische Untersuchung war unauffällig und die Blutkonzentrationen von kardialem Troponin I, Gesamtthyroxin sowie Taurin lagen in den jeweiligen Normbereichen. Die Katze wurde mit Sotalol (2.1 mg/kg zweimal täglich, per os) behandelt, was allerdings nicht zur gewünschten Kontrolle der Arrhythmie führte, wie bei wiederholten Untersuchungen innerhalb einer zweijährigen Zeitperiode festgestellt wurde. 24 Monate nach der Erstuntersuchung entwickelte die Katze Vorhofflimmern mit schneller Kammerfrequenz (200 bis 300 min–1). Ausserdem lag eine schwere Dilatation der Herzkammern mit systolischer Dysfunktion vor. Die Katze entwickelte Herzinsuffizienz und kardiogenen Schock und wurde auf Wunsch des Besitzers 27 Monate nach Erstvorstellung euthanasiert. Die pathologisch-anatomische und histologische Untersuchung des Herzens war unauffällig, wobei die klassischen primären Kardiomyopathien der Katze mit Sicherheit ausgeschlossen werden konnten. Die lange Dauer der Tachyarrhythmie, die progressiven strukturellen und funktionellen Veränderungen des Herzens sowie die ähnlichen pathologischen und histologischen Befunde lassen auf das Vorliegen einer Tachykardie-induzierten Kardiomyopathie schliessen.

English, GermanEine 10-jährige männlich-kastrierte Kurzhaarkatze wurde wegen einer asymptomatischen Tachykardie vorgestellt, die erstmalig vor zwei Wochen diagnostiziert worden war. Bei der elektrokardiographischen Untersuchung wurde ein normaler Sinusrhythmus mit atrialen Extraystolen und