|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) |

In algebra, the discriminant of a polynomial is a function of its coefficients, typically denoted by a capital 'D' or the capital Greek letter Delta (Δ). It gives information about the nature of its roots. Typically, the discriminant is zero if and only if the polynomial has a multiple root. For example, the discriminant of the quadratic polynomial

is

Here for real a, b and c, if Δ > 0, the polynomial has two real roots, if Δ = 0, the polynomial has one real double root, and if Δ < 0, the two roots of the polynomial are complex conjugates.

The discriminant of the cubic polynomial

is

For higher degrees, the discriminant is always a polynomial function of the coefficients. It becomes significantly longer for the higher degrees. The discriminant of a general quartic has 16 terms,[1] that of a quintic has 59 terms,[2] that of a 6th degree polynomial has 246 terms,[3] and the number of terms increases exponentially with the degree.[citation needed]

A polynomial has a multiple root (i.e. a root with multiplicity greater than one) in the complex numbers if and only if its discriminant is zero.

The concept also applies if the polynomial has coefficients in a field which is not contained in the complex numbers. In this case, the discriminant vanishes if and only if the polynomial has a multiple root in any algebraically closed field containing the coefficients.

As the discriminant is a polynomial function of the coefficients, it is defined as long as the coefficients belong to an integral domain R and, in this case, the discriminant is in R. In particular, the discriminant of a polynomial with integer coefficients is always an integer. This property is widely used in number theory.

The term "discriminant" was coined in 1851 by the British mathematician James Joseph Sylvester.[4]

Contents

- 1 Definition

- 2 Formulas for low degrees

- 3 Homogeneity

- 4 Quadratic formula

- 5 Discriminant of a polynomial

- 6 Nature of the roots

- 6.1 Quadratic

- 6.2 Cubic

- 6.3 Higher degrees

- 7 Discriminant of a polynomial over a commutative ring

- 8 Generalizations

- 8.1 Discriminant of a conic section

- 8.2 Discriminant of a quadratic form

- 8.3 Discriminant of an algebraic number field

- 9 Alternating polynomials

- 10 References

- 11 External links

Definition

In terms of the roots, the discriminant is given by

where is the leading coefficient and are the roots (counting multiplicity) of the polynomial in some splitting field. It is the square of the Vandermonde polynomial times .

As the discriminant is a symmetric function in the roots, it can also be expressed in terms of the coefficients of the polynomial, since the coefficients are the elementary symmetric polynomials in the roots; such a formula is given below.

Expressing the discriminant in terms of the roots makes its key property clear, namely that it vanishes if and only if there is a repeated root, but does not allow it to be calculated without factoring a polynomial, after which the information it provides is redundant (if one has the roots, one can tell if there are any duplicates). Hence the formula in terms of the coefficients allows the nature of the roots to be determined without factoring the polynomial.

Formulas for low degrees

The zero set of discriminant of the cubic , i.e. points satisfying

b2c2–4c3–4b3d–27d2+18bcd=0.

The discriminant of the quartic polynomial . The surface represents point (a,b,c) where the polynomial has a repeated roots, the cuspidal edge correspond to polynomials with a triple root and the self intersection to the polynomials with two different repeated roots.

The discriminant of a linear polynomial (degree 1) is rarely considered. If needed, it is commonly defined to be equal to 1 (this is compatible with the usual conventions for the empty product and the determinant of the empty matrix). There is no common convention for the discriminant of a constant polynomial (degree 0).

The quadratic polynomial

has discriminant

The cubic polynomial

has discriminant

The quartic polynomial

has discriminant

These are homogeneous polynomials in the coefficients, respectively of degree 2, 4 and 6. They are also homogeneous in terms of the roots, of respective degrees 2, 6 and 12.

Simpler polynomials have simpler expressions for their discriminants. For example, the monic quadratic polynomial x2 + bx + c has discriminant Δ = b2 − 4c. The monic cubic polynomial without quadratic term x3 + px + q has discriminant Δ = −4p3 − 27q2. In terms of the roots, these discriminants are homogeneous polynomials of respective degree 2 and 6.

Homogeneity

The discriminant is a homogeneous polynomial in the coefficients; it is also a homogeneous polynomial in the roots.

In the coefficients, the discriminant is homogeneous of degree 2n−2; this can be seen two ways. In terms of the roots-and-leading-term formula, multiplying all the coefficients by λ does not change the roots, but multiplies the leading term by λ. In terms of the formula as a determinant of a (2n−1) ×(2n−1) matrix divided by an, the determinant of the matrix is homogeneous of degree 2n−1 in the entries, and dividing by an makes the degree 2n−2; explicitly, multiplying the coefficients by λ multiplies all entries of the matrix by λ, hence multiplies the determinant by λ2n−1.

For a monic polynomial, the discriminant is a polynomial in the roots alone (as the an term is one), and is of degree n(n−1) in the roots, as there are terms in the product, each squared.

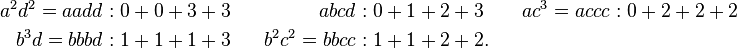

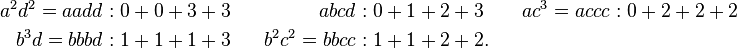

Let us consider the polynomial

It follows from what precedes that its discriminant is homogeneous of degree 2n−2 in the and quasi-homogeneous of weight n(n−1) if each is given the weight i. In other words, every monomial appearing in the discriminant satisfies the two equations

and

These thus correspond to the partitions of n(n−1) into at 2n−2 (non negative) parts of size at most n

This restricts the possible terms in the discriminant. For the quadratic polynomial there are only two possibilities for either [1,0,1] or [0,2,0], given the two monomials ac and b2. For the cubic polynomial , these are the partitions of 6 into 4 parts of size at most 3:

All these five monomials occur effectively in the discriminant.

While this approach gives the possible terms, it does not determine the coefficients. Moreover, in general not all possible terms will occur in the discriminant. The first example is for the quartic polynomial , in which case satisfies and , even though the corresponding discriminant does not involve the monomial .

Quadratic formula

The quadratic polynomial has discriminant

which is the quantity under the square root sign in the quadratic formula. For real numbers a, b, c, one has:

- When Δ > 0, P(x) has two distinct real roots

and its graph crosses the x-axis twice.

- When Δ = 0, P(x) has two coincident real roots

and its graph is tangent to the x-axis.

- When Δ < 0, P(x) has no real roots, and its graph lies strictly above or below the x-axis. The polynomial has two distinct complex roots

An alternative way to understand the discriminant of a quadratic is to use the characterization as "zero if and only if the polynomial has a repeated root". In that case the polynomial is The coefficients then satisfy so and a monic quadratic has a repeated root if and only if this is the case, in which case the root is Putting both terms on one side and including a leading coefficient yields

Discriminant of a polynomial

To find the formula for the discriminant of a polynomial in terms of its coefficients, it is easiest to introduce the resultant. Just as the discriminant of a single polynomial is the product of the square of the differences between distinct roots, the resultant of two polynomials is the product of the differences between their roots, and just as the discriminant vanishes if and only if the polynomial has a repeated root, the resultant vanishes if and only if the two polynomials share a root.

Since a polynomial has a repeated root if and only if it shares a root with its derivative the discriminant and the resultant both have the property that they vanish if and only if p has a repeated root, and they have almost the same degree (the degree of the resultant is one greater than the degree of the discriminant) and thus are equal up to a factor of degree one, which is, up to the sign, the leading coefficient of p.

The benefit of the resultant is that it can be computed as a determinant, namely as the determinant of the Sylvester matrix, a (2n − 1)×(2n − 1) matrix, whose first n – 1 rows contain the coefficients of p and the n last ones the coefficients of its derivative.

The resultant of the general polynomial

is equal to the determinant of the (2n − 1)×(2n − 1) Sylvester matrix:

The discriminant of is now given by the formula

For example, in the case n = 4, the above determinant is

The discriminant of the degree 4 polynomial is then obtained from this determinant upon dividing by .

In terms of the roots, the discriminant is equal to

where r1, ..., rn are the complex roots (counting multiplicity) of the polynomial:

This second expression makes it clear that p has a multiple root if and only if the discriminant is zero. (This multiple root can be complex.)

The discriminant can be defined for polynomials over arbitrary fields, in exactly the same fashion as above. The product formula involving the roots ri remains valid; the roots have to be taken in some splitting field of the polynomial. The discriminant can even be defined for polynomials over any commutative ring. However, if the ring is not an integral domain, above division of the resultant by should be replaced by substituting by 1 in the first column of the matrix.

Nature of the roots

The discriminant gives additional information on the nature of the roots beyond simply whether there are any repeated roots: for polynomials with real coefficients, it also gives information on whether the roots are real or complex. This is most transparent and easily stated for quadratic and cubic polynomials; for polynomials of degree 4 or higher this is more difficult to state.

Quadratic

Because the quadratic formula expressed the roots of a quadratic polynomial as a rational function in terms of the square root of the discriminant, the roots of a quadratic polynomial are in the same field as the coefficients if and only if the discriminant is a square in the field of coefficients: in other words, the polynomial factors over the field of coefficients if and only if the discriminant is a square.

As a real number has real square roots if and only if it is nonnegative, and these roots are distinct if and only if it is positive (not zero), the sign of the discriminant allows a complete description of the nature of the roots of a quadratic polynomial with real coefficients: [5]

- Δ > 0: 2 distinct real roots: factors over the reals;

- Δ < 0: 2 distinct complex roots (complex conjugate), does not factor over the reals;

- Δ = 0: 1 real root with multiplicity 2: factors over the reals as a square.

Further, for a quadratic polynomial with rational coefficients, it factors over the rationals if and only if the discriminant – which is necessarily a rational number, being a polynomial in the coefficients – is in fact a square.

Cubic

For more details on this topic, see Cubic polynomial § The nature of the roots.

For a cubic polynomial with real coefficients, the discriminant reflects the nature of the roots as follows: [6]

- Δ > 0: the equation has 3 distinct real roots;

- Δ < 0, the equation has 1 real root and 2 complex conjugate roots;

- Δ = 0: at least 2 roots coincide, and they are all real.

- It may be that the equation has a double real root and another distinct single real root; alternatively, all three roots coincide yielding a triple real root.

If a cubic polynomial has a triple root, it is a root of its derivative and of its second derivative, which is linear. Thus to decide if a cubic polynomial has a triple root or not, one may compute the root of the second derivative and look if it is a root of the cubic and of its derivative.

Higher degrees

More generally, for a polynomial of degree n with real coefficients, we have

- Δ > 0: for some integer k such that , there are 2k pairs of complex conjugate roots and n − 4k real roots, all different;

- Δ < 0: for some integer k such that , there are 2k + 1 pairs of complex conjugate roots and n − 4k − 2 real roots, all different;

- Δ = 0: at least 2 roots coincide, which may be either real or not real (in this case their complex conjugates also coincide).

Discriminant of a polynomial over a commutative ring

The definition of the discriminant of a polynomial in terms of the resultant may easily be extended to polynomials whose coefficients belong to any commutative ring. However, as the division is not always defined in such a ring, instead of dividing the determinant by the leading coefficient, one substitutes the leading coefficient by 1 in the first column of the determinant. This generalized discriminant has the following property which is fundamental in algebraic geometry.

Let f be a polynomial with coefficients in a commutative ring A and D its discriminant. Let φ be a ring homomorphism of A into a field K and φ(f) be the polynomial over K obtained by replacing the coefficients of f by their images by φ. Then φ(D) = 0 if and only if either the difference of the degrees of f and φ(f) is at least 2 or φ(f) has a multiple root in an algebraic closure of K. The first case may be interpreted by saying that φ(f) has a multiple root at infinity.

The typical situation where this property is applied is when A is a (univariate or multivariate) polynomial ring over a field k and φ is the substitution of the indeterminates in A by elements of a field extension K of k.

For example, let f be a bivariate polynomial in X and Y with real coefficients, such that f = 0 is the implicit equation of a plane algebraic curve. Viewing f as a univariate polynomial in Y with coefficients depending on X, then the discriminant is a polynomial in X whose roots are the X-coordinates of the singular points, of the points with a tangent parallel to the Y-axis and of some of the asymptotes parallel to the Y-axis. In other words the computation of the roots of the Y-discriminant and the X-discriminant allows to compute all remarkable points of the curve, except the inflection points.

Generalizations

The concept of discriminant has been generalized to other algebraic structures besides polynomials of one variable, including conic sections, quadratic forms, and algebraic number fields. Discriminants in algebraic number theory are closely related, and contain information about ramification. In fact, the more geometric types of ramification are also related to more abstract types of discriminant, making this a central algebraic idea in many applications.

Discriminant of a conic section

For a conic section defined in plane geometry by the real polynomial

the discriminant is equal to[7]

and determines the shape of the conic section. If the discriminant is less than 0, the equation is of an ellipse or a circle. If the discriminant equals 0, the equation is that of a parabola. If the discriminant is greater than 0, the equation is that of a hyperbola. This formula will not work for degenerate cases (when the polynomial factors).

Discriminant of a quadratic form

There is a substantive generalization to quadratic forms Q over any field K of characteristic ≠ 2. For characteristic 2, the corresponding invariant is the Arf invariant.

Given a quadratic form Q, the discriminant or determinant is the determinant of a symmetric matrix S for Q.[8]

Change of variables by a matrix A changes the matrix of the symmetric form by ATSA, which has determinant (det A)2 det S, so under change of variables, the discriminant changes by a non-zero square, and thus the class of the discriminant is well-defined in K/(K×)2, i.e., up to non-zero squares. See also Quadratic residue.

Less intrinsically, by a theorem of Jacobi, quadratic forms on can be expressed, after a linear change of variables, in diagonal form as

More precisely, a quadratic forms on V may be expressed as a sum

where the Li are independent linear forms and n is the number of the variables (some of the ai may be zero). Then the discriminant is the product of the ai, which is well-defined as a class in K/(K×)2.

For K = R, the real numbers, (R×)2 is the positive real numbers (any positive number is a square of a non-zero number), and thus the quotient R/(R×)2 has three elements: positive, zero, and negative. This is a cruder invariant than signature (n0, n+, n−), where n0 is the number of 0s and n± is the number of ±1s in diagonal form. The discriminant is then zero if the form is degenerate (n0 > 0), and otherwise it is the parity of the number of negative coefficients, (−1)n−.

For K = C, the complex numbers, (C×)2 is the non-zero complex numbers (any complex number is a square), and thus the quotient C/(C×)2 has two elements: non-zero and zero.

This definition generalizes the discriminant of a quadratic polynomial, as the polynomial homogenizes to the quadratic form which has symmetric matrix

whose determinant is . Up to a factor of −4, this is .

The invariance of the class of the discriminant of a real form (positive, zero, or negative) corresponds to the corresponding conic section being an ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola.

Discriminant of an algebraic number field

Main article: Discriminant of an algebraic number field

Alternating polynomials

Main article: Alternating polynomials

|

This section requires expansion. (December 2008) |

The discriminant is a symmetric polynomial in the roots; if one adjoins a square root of it (halves each of the powers: the Vandermonde polynomial) to the ring of symmetric polynomials in n variables , one obtains the ring of alternating polynomials, which is thus a quadratic extension of .

References

- ^ Wang, Dongming (2004). Elimination practice: software tools and applications. Imperial College Press. p. 180. ISBN 1-86094-438-8. , Chapter 10 page 180

- ^ Gelfand, I. M.; Kapranov, M. M.; Zelevinsky, A. V. (1994). Discriminants, resultants and multidimensional determinants. Birkhäuser. p. 1. ISBN 3-7643-3660-9. , Preview page 1

- ^ Dickenstein, Alicia; Emiris, Ioannis Z. (2005). Solving polynomial equations: foundations, algorithms, and applications. Springer. p. 26. ISBN 3-540-24326-7. , Chapter 1 page 26

- ^ J. J. Sylvester (1851) "On a remarkable discovery in the theory of canonical forms and of hyperdeterminants," Philosophical Magazine, 4th series, 2 : 391-410; Sylvester coins the word "discriminant" on page 406.

- ^ Irving, Ronald S. (2004), Integers, polynomials, and rings, Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., ISBN 0-387-40397-3 , Chapter 10.3 pp. 153–154

- ^ Irving, Ronald S. (2004), Integers, polynomials, and rings, Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., ISBN 0-387-40397-3 , Chapter 10 ex 10.14.4 and 10.17.4, pp. 154–156

- ^ Fanchi, John R. (2006), Math refresher for scientists and engineers, John Wiley and Sons, pp. 44–45, ISBN 0-471-75715-2 , Section 3.2, page 45

- ^ Cassels, J.W.S. (1978). Rational Quadratic Forms. London Mathematical Society Monographs 13. Academic Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-12-163260-1. Zbl 0395.10029.

External links

- Mathworld article

- Planetmath article