|

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2011) |

β− decay in an atomic nucleus (the accompanying antineutrino is omitted). The inset shows beta decay of a free neutron. In both processes, the intermediate emission of a virtual

W− boson (which then decays to electron and antineutrino) is not shown.

| Nuclear physics |

|

| Nucleus · Nucleons (p, n) · Nuclear force · Nuclear reaction |

Nuclear models and stability

Liquid drop · Nuclear shell · Nuclear structure

Binding energy · p–n ratio · Drip line · Stability Isl.

|

Nuclides' classification

Isotopes – equal Z

Isobars – equal A

Isotones – equal N

Isodiaphers – equal N − Z

Isomers – equal all the above

Mirror nuclei – Z ↔ N

Stable · Magic · Even/odd · Halo

|

Radioactive decay

Alpha α · Beta β (2β, β +) · K/L capture · Isomeric (Gamma γ · Internal conversion) · Spontaneous fission · Cluster decay · Neutron emission · Proton emission

Decay energy · Decay chain · Decay product · Radiogenic nuclide

|

Nuclear fission

Spontaneous · Products (pair breaking) · Photofission

|

Capturing processes

electron · neutron (s · r) · proton (p · rp)

|

High energy processes

Spallation (by cosmic ray) · Photodisintegration

|

Nucleosynthesis topics

Nuclear fusion

Processes: Stellar · Big Bang · Supernova

Nuclides: Primordial · Cosmogenic · Artificial

|

Scientists

Becquerel · Davisson · Bethe · Skłodowska-Curie · Pi.Curie · Fr.Curie · Ir.Curie · Fermi · Oppenheimer · Rutherford · Thomson · Chadwick · Oliphant · Szilárd · Teller · Lawrence · Proca · Mayer · Jensen · Alvarez · Soddy · Rabi · Meitner · Strassmann · Hahn · Purcell · Walton · Cockcroft ·

|

|

|

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which a beta particle (an electron or a positron) is emitted from an atomic nucleus. Beta decay is a process which allows the atom to obtain the optimal ratio of protons and neutrons.[1]

There are two types of beta decay, a decay that is mediated by the weak force: beta minus and beta plus. In the case of beta decay that produces an electron emission, it is referred to as beta minus (β−), while in the case of a positron emission as beta plus (β+).

An example of β− decay is shown when carbon-14 decays into nitrogen-14:

- 14

6C → 14

7N + e− + ν

e

Notice how, in electron emission, an electron antineutrino is also emitted. In this form of decay, the original element has decayed into a new element with an unchanged mass number A but an atomic number Z that has increased by one.

An example of positron (β+ decay) is shown with magnesium-23 decaying into sodium-23:

- 23

12Mg → 23

11Na + e+ + ν

e

In contrast to electron emission, positron emission is accompanied by the emission of an electron neutrino. Similar to electron emission, positron decay results in nuclear transmutation, changing an atom of a chemical element into an atom of an element with an unchanged mass number. However, in positron decay, the resulting element has an atomic number that has decreased by one.

Emitted beta particles have a continuous kinetic energy spectrum, ranging from 0 to the maximal available energy (Q), which depends on the parent and daughter nuclear states that participate in the decay. The continuous energy spectra of beta particle occurs because Q is shared between beta particle and a neutrino.[2] A typical Q is around 1 MeV, but it can range from a few keV to a few tens of MeV. Since the rest mass energy of the electron is 511 keV, the most energetic beta particles are ultrarelativistic, with speeds very close to the speed of light.

Sometimes electron capture decay is included as a type of beta decay (and is referred to as "inverse beta decay"), because the basic process, mediated by the weak force is the same. However, no beta particle is emitted, but only an electron neutrino. Instead of beta-plus emission, an inner atomic electron is captured by a proton in the nucleus. An example of electron capture involves krypton-81 becoming bromine-81 and producing an electron neutrino:

- 81

36Kr + e− → 81

35Br + ν

e

This type of decay is therefore analogous to positron emission (and also happens, as an alternative decay route, in all positron-emitters). However, the route of electron capture is the only type of decay that is allowed in proton-rich nuclides that do not have sufficient energy to emit a positron (and neutrino). These may still reach a lower energy state, by the equivalent process of electron capture and neutrino emission.

|

Contents

- 1 β− decay

- 2 β+ decay

- 3 Electron capture (K-capture)

- 4 Nuclear transmutation

- 5 Double beta decay

- 6 Bound-state β− decay

- 7 Forbidden transitions

- 8 Beta emission spectrum

- 8.1 Fermi function

- 8.2 Kurie plot

- 9 History

- 9.1 Discovery and characterization of β− decay

- 9.2 Neutrinos in beta decay

- 9.3 Discovery of other types of beta decay

- 9.4 The rate of beta decay may vary

- 10 See also

- 11 References

- 12 External links

|

β− decay [edit]

The Feynman diagram for

β− decay of a neutron into a proton, electron, and electron antineutrino via an intermediate

W− boson.

In β− decay, the weak interaction converts an atomic nucleus into a nucleus with one higher atomic number while emitting an electron (e−) and an electron antineutrino (ν

e):

- A

ZN → A

Z+1N’ + e− + ν

e [1]

where A and Z are the mass number and atomic number of the decaying nucleus.

Another example is when the free neutron (1

0n) decays by β− decay into a proton (p):

- n → p + e− + ν

e.

At the fundamental level (as depicted in the Feynman diagram on the right), this is caused by the conversion of the negatively charged down quark to the positively charged up quark by emission of a W− boson; the W− boson subsequently decays into an electron and an electron antineutrino:

- d → u + e− + ν

e.

β− decay generally occurs in neutron-rich nuclei.

β+ decay [edit]

Main article: Positron emission

Energy spectrum of beta particle in beta decay

In β+ decay, or "positron emission", the weak interaction converts a nucleus into its next-lower neighbor on the periodic table while emitting a positron (e+) and an electron neutrino (ν

e):

- A

ZN → A

Z−1N’ + e+ + ν

e [1]

β+ decay cannot occur in an isolated proton because it requires energy due to the mass of the neutron being greater than the mass of the proton. β+ decay can only happen inside nuclei when the daughter nucleus has a greater binding energy (and therefore a lower total energy) than the mother nucleus. The difference between these energies goes into the reaction of converting a proton into a neutron, a positron and a neutrino and into the kinetic energy of these particles. In an opposite process to negative beta decay, the weak interaction converts a proton into a neutron by converting an up quark into a down quark by having it emit a W+ or absorb a W−.

Electron capture (K-capture) [edit]

Main article: Electron capture

In all cases where β+ decay of a nucleus is allowed energetically, the electron capture process is also allowed, in which the same nucleus captures an atomic electron with the emission of a neutrino:

- A

ZN + e− → A

Z−1N’ + ν

e

The emitted neutrino is mono-energetic. In proton-rich nuclei where the energy difference between initial and final states is less than 2mec2, β+ decay is not energetically possible, and electron capture is the sole decay mode.

This decay is also called K-capture because the innermost electron of an atom belongs to the K-shell of the electronic configuration of the atom, and this has the highest probability to interact with the nucleus.

There is an analogous process possible in theory in antimatter: antiproton-rich antimatter radioisotopes might decay via an analogous process of positron capture[citation needed], but in practice no such complex antimatter nuclides have either been discovered or artificially constructed.

Nuclear transmutation [edit]

If the proton and neutron are part of an atomic nucleus, these decay processes transmute one chemical element into another. For example:

-

137

55Cs |

|

|

→ |

137

56Ba |

+ |

e− |

+ |

ν

e |

(beta minus decay) |

22

11Na |

|

|

→ |

22

10Ne |

+ |

e+ |

+ |

ν

e |

(beta plus decay) |

22

11Na |

+ |

e− |

→ |

22

10Ne |

+ |

ν

e |

|

|

(electron capture) |

Beta decay does not change the number A of nucleons in the nucleus but changes only its charge Z. Thus the set of all nuclides with the same A can be introduced; these isobaric nuclides may turn into each other via beta decay. Among them, several nuclides (at least one for any given mass number A) are beta stable, because they present local minima of the mass excess: if such a nucleus has (A, Z) numbers, the neighbour nuclei (A, Z−1) and (A, Z+1) have higher mass excess and can beta decay into (A, Z), but not vice versa. For all odd mass numbers A the global minimum is also the unique local minimum. For even A, there are up to three different beta-stable isobars experimentally known; for example, 96

40Zr, 96

42Mo, and 96

44Ru are all beta-stable, though the first one can undergo a very rare double beta decay (see below). There are about 355 known beta-decay stable nuclides total.

Usually unstable nuclides are clearly either "neutron rich" or "proton rich", with the former undergoing beta decay and the latter undergoing electron capture (or more rarely, due to the higher energy requirements, positron decay). However, in a few cases of odd-proton, odd-neutron radionuclides, it may be energetically favorable for the radionuclide to decay to an even-proton, even-neutron isobar either by undergoing beta-positive or beta-negative decay. An often-cited example is 64

29Cu, which decays by positron emission 61% of the time to 64

28Ni, and 39% of the time by (negative) beta decay to 64

30Zn.

A beta-stable nucleus may undergo other kinds of radioactive decay (alpha decay, for example). In nature, most isotopes are beta stable, but a few exceptions exist with half-lives so long that they have not had enough time to decay since the moment of their nucleosynthesis. One example is the odd-proton odd-neutron nuclide 40

19K, which undergoes all three types of beta decay (β−, β+ and electron capture) with a half-life of 1.277×109 years.

Double beta decay [edit]

Main article: Double beta decay

Some nuclei can undergo double beta decay (ββ decay) where the charge of the nucleus changes by two units. Double beta decay is difficult to study in most practically interesting cases, because both β decay and ββ decay are possible, with probability favoring β decay; the rarer ββ decay process is masked by these events. Thus, ββ decay is usually studied only for beta stable nuclei. Like single beta decay, double beta decay does not change A; thus, at least one of the nuclides with some given A has to be stable with regard to both single and double beta decay.

Bound-state β− decay [edit]

For fully ionized atoms (bare nuclei), it is possible for electrons to be emitted from the nucleus into low-lying atomic bound states (orbitals). This can not occur for neutral atoms whose low-lying bound states are already filled.

The phenomenon was first observed for 163Dy66+ in 1992 by Jung et al. of the Darmstadt Heavy-Ion Research group. Although neutral 163Dy is a stable isotope, the fully ionized 163Dy66+ undergoes β decay into the K and L shells with a half-life of 47 days.[3]

Another possibility is that a fully ionized atom undergoes greatly accelerated β decay, as observed for 187Re by Bosch et al., also at Darmstadt. Neutral 187Re does undergo β decay with a half-life of 42 × 109 years, but for fully ionized 187Re75+ this is shortened by a factor of 109 to only 32.9 years.[4] For comparison the variation of decay rates of other nuclear processes due to chemical environment is less than 1%. (See Radioactive decay#Changing decay rates)

Forbidden transitions [edit]

Beta decays can be classified according to the L-value of the emitted radiation. When L > 0, the decay is referred to as "forbidden". Nuclear selection rules require high L-values to be accompanied by changes in nuclear spin (J) and parity (π). The selection rules for the Lth forbidden transitions are:

where Δπ = 1 or −1 corresponds to no parity change or parity change, respectively. The special case of a 0+ → 0+ transition (which in gamma decay is absolutely forbidden) is referred to as "superallowed" for beta decay, and proceeds very quickly by this decay route. The following table lists the ΔJ and Δπ values for the first few values of L:

| Forbiddenness |

ΔJ |

Δπ |

| Superallowed |

0+ → 0+ |

no |

| Allowed |

0, 1 |

no |

| First forbidden |

0, 1, 2 |

yes |

| Second forbidden |

1, 2, 3 |

no |

| Third forbidden |

2, 3, 4 |

yes |

Beta emission spectrum [edit]

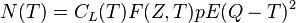

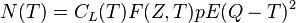

Beta decay can be considered as a perturbation as described in quantum mechanics, and thus Fermi's Golden Rule can be applied. This leads to an expression for the kinetic energy spectrum N(T) of emitted betas as follows:[5]

where T is the kinetic energy, CL is a shape function that depends on the forbiddenness of the decay (it is constant for allowed decays), F(Z, T) is the Fermi Function (see below) with Z the charge of the final-state nucleus, E = T + m c2 is the total energy, p =√(E ∕ c)2 − (m c)2 is the momentum, and Q is the Q value of the decay. The kinetic energy of the emitted neutrino is given approximately by Q minus the kinetic energy of the beta.

Fermi function [edit]

The Fermi function that appears in the beta spectrum formula accounts for the Coulomb attraction / repulsion between the emitted beta and the final state nucleus. Approximating the associated wavefunctions to be spherically symmetric, the Fermi function can be analytically calculated to be:[6]

where S =√1 − α2 Z2 (α is the fine-structure constant), η = ± α Z E ∕ p c (+ for electrons, − for positrons), ρ = rN ∕ ℏ (rN is the radius of the final state nucleus), and Γ is the Gamma function.

For non-relativistic betas (Q ≪ mec2), this expression can be approximated by:[7]

Other approximations can be found in the literature.[8]

Kurie plot [edit]

A Kurie plot (also known as a Fermi–Kurie plot) is a graph used in studying beta decay developed by Franz N. D. Kurie, in which the square root of the number of beta particles whose momenta (or energy) lie within a certain narrow range, divided by the Fermi function, is plotted against beta-particle energy. It is a straight line for allowed transitions and some forbidden transitions, in accord with the Fermi beta-decay theory. The energy-axis (x-axis) intercept of a Kurie plot corresponds to the maximum energy imparted to the electron/positron (the decay's Q-value).

History [edit]

Discovery and characterization of β− decay [edit]

Radioactivity was discovered in 1896 by Henri Becquerel in uranium, and subsequently observed by Marie and Pierre Curie in thorium and in the new elements polonium and radium. In 1899 Ernest Rutherford separated radioactive emissions into two types: alpha and beta (now beta minus), based on penetration of objects and ability to cause ionization. Alpha rays could be stopped by thin sheets of paper or aluminium, whereas beta rays could penetrate several millimetres of aluminium. (In 1900 Paul Villard identified a still more penetrating type of radiation, which Rutherford identified as a fundamentally new type in 1903, and termed gamma rays).

In 1900 Becquerel measured the mass-to-charge ratio (m ∕ e) for beta particles by the method of J.J. Thomson used to study cathode rays and identify the electron. He found that m ∕ e for a beta particle is the same as for Thomson’s electron, and therefore suggested that the beta particle is in fact an electron.

In 1901 Rutherford and Frederick Soddy showed that alpha and beta radioactivity involves the transmutation of atoms into atoms of other chemical elements. In 1913, after the products of more radioactive decays were known, Soddy and Kazimierz Fajans independently proposed their radioactive displacement law, which states that beta (i.e. β−) emission from one element produces another element one place to the right in the periodic table, while alpha emission produces an element two places to the left.

Neutrinos in beta decay [edit]

Historically, the study of beta decay provided the first physical evidence of the neutrino. In 1911 Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn performed an experiment that showed that the energies of electrons emitted by beta decay had a continuous rather than discrete spectrum. This was in apparent contradiction to the law of conservation of energy, as it appeared that energy was lost in the beta decay process. A second problem was that the spin of the nitrogen-14 atom was 1, in contradiction to the Rutherford prediction of ½.

In 1920–1927, Charles Drummond Ellis (along with James Chadwick and colleagues) established clearly that the beta decay spectrum is really continuous, ending all controversies. It also had an effective upper bound in energy, which was a severe blow to Bohr's suggestion that conservation of energy might be true only in a statistical sense, and might be violated in any given decay. Now the problem of how to account for the variability of energy in known beta decay products, as well as for conservation of momentum and angular momentum in the process, became acute.

In a famous letter written in 1930 Wolfgang Pauli suggested that in addition to electrons and protons atoms also contained an extremely light neutral particle which he called the neutron. He suggested that this "neutron" was also emitted during beta decay (thus accounting for the known missing energy, momentum, and angular momentum) and had simply not yet been observed. In 1931 Enrico Fermi renamed Pauli's "neutron" to neutrino, and in 1934 Fermi published a very successful model of beta decay in which neutrinos were produced. The neutrino interaction with matter was so weak that detecting it proved a severe experimental challenge, and was not accomplished until 1956. However, the properties of neutrinos were (with a few minor modifications) as predicted by Pauli and Fermi.

Discovery of other types of beta decay [edit]

In 1934 Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie bombarded aluminium with alpha particles to effect the nuclear reaction 4

2He + 27

13Al → 30

15P + 1

0n, and observed that the product isotope 30

15P emits a positron identical to those found in cosmic rays by Carl David Anderson in 1932. This was the first example of β+ decay (positron emission), which they termed artificial radioactivity since 30

15P is a short-lived nuclide which does not exist in nature.

The theory of electron capture was first discussed by Gian-Carlo Wick in a 1934 paper, and then developed by Hideki Yukawa and others. K-electron capture was first observed in 1937 by Luis Alvarez, in the nuclide 48V.[9][10][11] Alvarez went on to study electron capture in 67Ga and other nuclides.[9][12][13]

The rate of beta decay may vary [edit]

The rate of beta decay for an isotope was believed to be constant, no matter the conditions. (That is, unchanged by temperature, pressure, etc.) A paper in May 2012 presented data that the rate of gamma radiation – the result of beta decay – did change over time. The rate went up and down with the time of day, time of year, and other periods. The researchers linked these periods of the sun (e.g., the sun's rotation relative to the earth) and hypothesized that the supply of neutrinos coming from the sun was affecting the rate of beta decay. There is no theory for why neutrinos should affect beta decay rates; so far, this newly-measured effect has no explanation.[14]

See also [edit]

- Double beta decay

- Electron capture

- Neutrino

- Alpha decay

- Betavoltaics

- Particle radiation

- Radionuclide

- Tritium illumination, a form of fluorescent lighting powered by beta decay

References [edit]

- Franz N. D. Kurie, J. R. Richardson, H. C. Paxton (March 1936). "The Radiations Emitted from Artificially Produced Radioactive Substances. I. The Upper Limits and Shapes of the β-Ray Spectra from Several Elements". Physical Review 49 (5): 368–381. Bibcode:1936PhRv...49..368K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.49.368.

- F. N. D. Kurie (May 1948). "On the Use of the Kurie Plot". Physical Review 73 (10): 1207. Bibcode:1948PhRv...73.1207K. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.73.1207.

- Jagdish K. Tuli, Nuclear Wallet Cards, 7th edition, April 2005, Brookhaven National Laboratory, US National Nuclear Data Center

- ^ a b c Konya, Jozsef (2012). Nuclear and Radiochemistry. Elsevier. p. 74. ISBN 9780123914873.

- ^ Konya, Jozsef (2012). Nuclear and Radiochemistry. Elsevier. p. 75. ISBN 9780123914873.

- ^ M. Jung et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 2164 (1992) First observation of bound-state beta minus decay.

- ^ F. Bosch et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 5190 (1996) Observation of bound-state beta minus decay of fully ionized 187Re: 187Re–187Os Cosmochronometry

- ^ Energy and Momentum Spectra for Beta Decay, accessed on line March 9, 2012.

- ^ E. Fermi, Z. Phys. 88, 161 (1934).

- ^ N. F. Mott and H. S. W. Massey, The Theory of Atomic Collisions, Clarendon, Oxford (1933).

- ^ P. Venkataramaiah et al., J. Phys. G: Nucl. Phys. 11, 359 (1985); G. K. Schenter and P. Vogel, Nucl. Sci. Eng. 83, 393 (1983).

- ^ a b pp. 11–12, K-Electron Capture by Nuclei, Emilio Segré, chapter 3 in Discovering Alvarez: selected works of Luis W. Alvarez, with commentary by his students and colleagues, Luis W. Alvarez and W. Peter Trower, University of Chicago Press, 1987, ISBN 0-226-81304-5.

- ^ Luis Alvarez, The Nobel Prize in Physics 1968, biography, nobelprize.org. Accessed on line October 7, 2009.

- ^ Nuclear K Electron Capture, Luis W. Alvarez, Physical Review 52 (1937), pp. 134–135, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.52.134 .

- ^ Electron Capture and Internal Conversion in Gallium 67, Luis W. Alvarez, Physical Review 53 (1937), p. 606, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.53.606.

- ^ The Capture of Orbital Electrons by Nuclei, Luis W. Alvarez, Physical Review 54 (October 1, 1938), pp. 486–497, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.54.486.

- ^ Peter A. Sturrock, Gideon Steinitz, Ephraim Fischbach, Daniel Javorsek, II, Jere H. Jenkins, Analysis of Gamma Radiation from a Radon Source: Indications of a Solar Influence, Accessed on line September 2, 2012.

External links [edit]

- The Live Chart of Nuclides - IAEA with filter on decay type

Definition of Beta Disintegration (Decay) at Science Dictionary

|

Nuclear processes

|

|

| Radioactive decay |

- Alpha decay

- Beta decay

- Gamma radiation

- Cluster decay

- Double beta decay

- Double electron capture

- Internal conversion

- Isomeric transition

- Spontaneous fission

|

|

| Stellar nucleosynthesis |

- Deuterium burning

- Lithium burning

- pp-chain

- CNO cycle

- α process

- Triple-α

- C burning

- Ne burning

- O burning

- Si burning

- R-process

- S-process

- P-process

- Rp-process

|

|

| Other processes |

|

Emission

|

- Neutron emission

- Positron emission

- Proton emission

|

|

|

Capture

|

- Electron capture

- Neutron capture

|

|

|