Incoming light in the parallel (

s) polarization sees a different effective index of refraction than light in the perpendicular (

p) polarization, and is thus refracted at a different angle.

A calcite crystal laid upon a graph paper with blue lines showing the double refraction

Doubly refracted image as seen through a calcite crystal, seen through a rotating polarizing filter illustrating the opposite polarization states of the two images.

Birefringence is the optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light.[1] These optically anisotropic materials are said to be birefringent (or birefractive). The birefringence is often quantified as the maximum difference between refractive indices exhibited by the material. Crystals with asymmetric crystal structures are often birefringent, as are plastics under mechanical stress.

Birefringence is responsible for the phenomenon of double refraction whereby a ray of light, when incident upon a birefringent material, is split by polarization into two rays taking slightly different paths. This effect was first described by the Danish scientist Rasmus Bartholin in 1669, who observed it[2] in calcite, a crystal having one of the strongest birefringences. However it was not until the 19th century that Augustin-Jean Fresnel described the phenomenon in terms of polarization, understanding light as a wave with field components in transverse polarizations (perpendicular to the direction of the wave vector).

Contents

- 1 Explanation

- 1.1 Biaxial materials

- 1.2 Double refraction

- 2 Terminology

- 2.1 Fast and slow rays

- 2.2 Positive or negative

- 3 Sources of optical birefringence

- 4 Common birefringent materials

- 5 Measurement

- 6 Applications

- 6.1 Medicine

- 6.2 Stress induced birefringence

- 6.3 Other cases of birefringence

- 7 Theory

- 8 See also

- 9 References

- 10 External links

Explanation

The simplest (and most common) type of birefringence is described as uniaxial, meaning that there is a single direction governing the optical anisotropy whereas all directions perpendicular to it (or at a given angle to it) are optically equivalent. Thus rotating the material around this axis does not change its optical behavior. This special direction is known as the optic axis of the material. Light whose polarization is perpendicular to the optic axis is governed by a refractive index no (for "ordinary"). Light whose polarization is in the direction of the optic axis sees an optical index ne (for "extraordinary"). For any ray direction there will be a polarization direction perpendicular to the optic axis, and this is called an ordinary ray. However, for most ray directions the other polarization direction will be partly in the direction of the optic axis, and this is called an extraordinary ray. The ordinary ray will always experience a refractive index of no, whereas the refractive index of the extraordinary ray will be in between no and ne, depending on the ray direction as described by the index ellipsoid. The magnitude of the difference is quantified by the birefringence:

- .

The propagation (as well as reflection coefficient) of the ordinary ray is simply described by no as if there were no birefringence involved. However the extraordinary ray, as its name suggests, propagates unlike any wave in a homogenous optical material. Its refraction (and reflection) at a surface can be understood using the effective refractive index (a value in between no and ne). However it is in fact an inhomogeneous wave whose power flow (given by the Poynting vector) is not exactly in the direction of the wave vector. This causes an additional shift in that beam, even when launched at normal incidence, as is popularly observed using a crystal of calcite as photographed above. Rotating the calcite crystal will cause one of the two images, that of the extraordinary ray, to rotate slightly around that of the ordinary ray which remains fixed.

When the light propagates either along or orthogonal to the optic axis, such a lateral shift does not occur. In the first case, both polarizations see the same effective refractive index, so there is no extraordinary ray. In the second case the extraordinary ray propagates at a different phase velocity (corresponding to ne) but is not an inhomogeneous wave. A crystal with its optic axis in this orientation, parallel to the optical surface, may be used to create a waveplate, in which there is no distortion of the image but an intentional modification of the state of polarization of the incident wave. For instance, a quarter-wave plate is commonly used to create circular polarization from a linearly polarized source.

Biaxial materials

The case of so-called biaxial crystals is substantially more complex.[3] These are characterized by three refractive indices corresponding to two principal axes of the crystal. For most ray directions, both polarizations would be classified as extraordinary rays but with different effective refractive indices. Being extraordinary waves, however, the direction of power flow is not identical to the direction of the wave vector in either case.

The two refractive indices can be determined using the index ellipsoid for waves with a given wave vector. Note that for biaxial crystals the index ellipsoid will not be an ellipsoid of revolution (or "spheroid") but is described by three unequal principle refractive indices nα, nβ and nγ. Thus there is no axis around which a rotation leaves the optical properties invariant (as there is with uniaxial crystals whose index ellipsoid is a spheroid).

Double refraction

When an arbitrary beam of light strikes the surface of a birefringent material, the polarizations corresponding to the ordinary and extraordinary rays generally take somewhat different paths. Unpolarized light consists of equal amounts of energy in any two orthogonal polarizations, and even polarized light (except in special cases) will have some energy in each of these polarizations. According to Snell's law of refraction, the angle of refraction will be governed by the effective refractive index which is different between these two polarizations. This is clearly seen, for instance, in the Wollaston prism which is designed to separate incoming light into two linear polarizations using a birefringent material such as calcite.

The different angles of refraction for the two polarization components are shown in the figure at the top of the page, with the optic axis along the surface (and perpendicular to the plane of incidence), so that the angle of refraction is different for the p polarization (the "ordinary ray" in this case, having its polarization perpendicular to the optic axis) and the s polarization (the "extraordinary ray" with a polarization component along the optic axis). In addition, a distinct form of double refraction occurs in cases where the optic axis is not along the refracting surface (nor exactly normal to it); in this case the electric polarization of the birefringent material is not exactly in the direction of the wave's electric field for the extraordinary ray. The direction of power flow (given by the Poynting vector) for this inhomogenous wave is at a finite angle from the direction of the wave vector resulting in an additional separation between these beams. So even in the case of normal incidence, where the angle of refraction is zero (according to Snell's law, regardless of effective index of refraction), the energy of the extraordinary ray may be propagated at an angle. This is commonly observed using a piece of calcite cut appropriately with respect to its optic axis, placed above a paper with writing, as in the above two photographs.

Terminology

Much of the work involving polarization preceded the understanding of light as a transverse electromagnetic wave, and this has affected some terminology in use. Isotropic materials have symmetry in all directions and the refractive index is the same for any polarization direction. An anisotropic material is called "birefringent" because it will generally refract a single incoming ray in two directions, which we now understand correspond to the two different polarizations. This is true of either a uniaxial or biaxial material.

In a uniaxial material, one ray behaves according to the normal law of refraction (corresponding to the ordinary refractive index), so an incoming ray at normal incidence remains normal to the refracting surface. However, as explained above, the other polarization can be deviated from normal incidence, which cannot be described using the law of refraction. This thus became known as the extraordinary ray. The terms "ordinary" and "extraordinary" are still applied to the polarization components perpendicular to and not perpendicular to the optic axis respectively, even in cases where no double refraction is involved.

A material is termed uniaxial when it has a single direction of symmetry in its optical behavior, which we term the optic axis. It also happens to be the axis of symmetry of the index ellipsoid (a spheroid in this case). The index ellipsoid could still be described according to the refractive indices, nα, nβ and nγ, along three coordinate axes, however in this case two are equal. So if nα = nβ corresponding to the x and y axes, then the extraordinary index is nγ corresponding to the z axis, which is also called the optic axis in this case.

However materials in which all three refractive indices are different are termed biaxial and the origin of this term is more complicated and frequently misunderstood. In a uniaxial crystal, different polarization components of a beam will travel at different phase velocities, except for rays in the direction of what we call the optic axis. Thus the optic axis has the particular property that rays in that direction do not exhibit birefringence, with all polarizations in such a beam experiencing the same index of refraction. It is very different when the three principal refractive indices are all different; then an incoming ray in any of those principle directions will still encounter two different refractive indices. But it turns out that there are two special directions (at an angle to all of the 3 axes) where the refractive indices for different polarizations are again equal. For this reason, these crystals were designated as biaxial, with the two "axes" in this case referring to ray directions in which propagation does not experience birefringence.

Fast and slow rays

In a birefringent material, a wave consists of two polarization components which generally are governed by different effective refractive indices. The so-called slow ray is the component for which the material has the higher effective refractive index (slower phase velocity), while the fast ray is the one with a lower effective refractive index. When a beam is incident on such a material from air (or any material with a lower refractive index), the slow ray is thus refracted more towards the normal than the fast ray. In the figure at the top of the page, it can be seen that refracted ray with s polarization in the direction of the optic axis (thus the extraordinary ray) is the slow ray in this case.

Using a thin slab of that material at normal incidence, one would implement a waveplate. In this case there is essentially no spatial separation between the polarizations, however the phase of the wave in the parallel polarization (the slow ray) will be retarded with respect to the perpendicular polarization. These directions are thus known as the slow axis and fast axis of the waveplate.

Positive or negative

Uniaxial birefringence is classified as positive when the extraordinary index of refraction ne is greater than the ordinary index no. Negative birefringence means that Δn = ne - no is less than zero.[4] In other words, the polarization of the fast (or slow) wave is perpendicular to the optic axis when the birefringence of the crystal is positive (or negative, respectively). In the case of biaxial crystals, all three of the principal axes have different refractive indices so this designation does not apply. But for any defined ray direction one can just as well designate the fast and slow ray polarizations.

Sources of optical birefringence

While birefringence is usually obtained using an anisotropic crystal, it can result from an optically isotropic material in a few ways:

- Stress birefringence results when isotropic materials are stressed or deformed such that the isotropy is lost in one direction (i.e., stretched or bent).

- Intrinsic birefringence, whereby the material has more than one chemical group with differing refractive indices that have some preferential order that results in optical rotation.

- Form birefringence, whereby structure elements, such as rods or spheres having one refractive index, are suspended in a media with a second refractive index.

- By the Kerr effect, whereby an applied electric field induces birefringence at optical frequencies through the effect of nonlinear optics;

- By the Faraday effect, where a magnetic field causes some materials to become circularly birefringent (having slightly different indices of refraction for left and right handed circular polarizations), making the material optically active until the field is removed;

- By the self or forced alignment into thin films of amphiphilic molecules such as lipids, some surfactants or liquid crystals

Common birefringent materials

The best-characterized birefringent materials are crystals. Due to their specific crystal structures their refractive indices are well defined. Depending on the symmetry of a crystal structure (as determined by one of the 219 possible crystallographic space groups), crystals in that group may be forced to be isotropic (not birefringent), to have uniaxial symmetry, or neither in which case it is a biaxial crystal. The crystal structures permitting uniaxial and biaxial birefringence are noted in the two tables, below, listing the two or three principle refractive indices (at wavelength 590 nm) of some better known crystals.[5]

Many plastics are birefringent, because their molecules are 'frozen' in a stretched conformation when the plastic is molded or extruded.[6] For example, ordinary cellophane is birefringent. Polarizers are routinely used to detect stress in plastics such as polystyrene and polycarbonate.

Cotton fiber is birefringent because of high levels of cellulosic material in the fiber's secondary cell wall.

Polarized light microscopy is commonly used in biological tissue, as many biological materials are birefringent. Collagen, found in cartilage, tendon, bone, corneas, and several other areas in the body, is birefringent and commonly studied with polarized light microscopy.[7] Some proteins are also birefringent, exhibiting form birefringence.[8]

Inevitable manufacturing imperfections in optical fiber leads to birefringence which is one cause of pulse broadening in fiber-optic communications. Such imperfections can be geometrical (lack of circular symmetry), due to stress applied to the optical fiber, and/or due to bending of the fiber. Birefringence is intentionally introduced (for instance, by making the cross-section elliptical) in order to produce polarization-maintaining optical fibers.

In addition to anisotropy in the electric polarizability (electric susceptibility), anisotropy in the magnetic polarizability (magnetic permeability) can also cause birefringence. However at optical frequencies, values of magnetic permeability for natural materials are not measurably different from µ0 so this is not a source of optical birefringence in practice.

Uniaxial crystals, at 590 nm[5]

| Material |

Crystal system |

no |

ne |

Δn |

| barium borate BaB2O4 |

Trigonal |

1.6776 |

1.5534 |

-0.1242 |

| beryl Be3Al2(SiO3)6 |

Hexagonal |

1.602 |

1.557 |

-0.045 |

| calcite CaCO3 |

Trigonal |

1.658 |

1.486 |

-0.172 |

| ice H2O |

Hexagonal |

1.309 |

1.313 |

+0.004 |

| lithium niobate LiNbO3 |

Trigonal |

2.272 |

2.187 |

-0.085 |

| magnesium fluoride MgF2 |

Tetragonal |

1.380 |

1.385 |

+0.006 |

| quartz SiO2 |

Trigonal |

1.544 |

1.553 |

+0.009 |

| ruby Al2O3 |

Trigonal |

1.770 |

1.762 |

-0.008 |

| rutile TiO2 |

Tetragonal |

2.616 |

2.903 |

+0.287 |

| sapphire Al2O3 |

Trigonal |

1.768 |

1.760 |

-0.008 |

| silicon carbide SiC |

Hexagonal |

2.647 |

2.693 |

+0.046 |

| tourmaline (complex silicate ) |

Trigonal |

1.669 |

1.638 |

-0.031 |

| zircon, high ZrSiO4 |

Tetragonal |

1.960 |

2.015 |

+0.055 |

| zircon, low ZrSiO4 |

Tetragonal |

1.920 |

1.967 |

+0.047 |

Biaxial crystals, at 590 nm[5]

| Material |

Crystal system |

nα |

nβ |

nγ |

| borax Na2(B4O5)(OH)4·8(H2O) |

Monoclinic |

1.447 |

1.469 |

1.472 |

| epsom salt MgSO4·7(H2O) |

Monoclinic |

1.433 |

1.455 |

1.461 |

mica, biotite K(Mg,Fe)

3AlSi

3O

10(F,OH)

2 |

Monoclinic |

1.595 |

1.640 |

1.640 |

| mica, muscovite KAl2(AlSi3O10)(F,OH)2 |

Monoclinic |

1.563 |

1.596 |

1.601 |

| olivine (Mg, Fe)2SiO4 |

Orthorhombic |

1.640 |

1.660 |

1.680 |

| perovskite CaTiO3 |

Orthorhombic |

2.300 |

2.340 |

2.380 |

| topaz Al2SiO4(F,OH)2 |

Orthorhombic |

1.618 |

1.620 |

1.627 |

| ulexite NaCaB5O6(OH)6•5(H2O) |

Triclinic |

1.490 |

1.510 |

1.520 |

Measurement

Birefringence and other polarization based optical effects (such as optical rotation and linear or circular dichroism) can be measured by measuring the changes in the polarization of light passing through the material. These measurements are known as polarimetry. Polarized light microscopes, which contain two polarizers that are at 90 degrees to each other on either side of the sample, are used to visualize birefringence. The addition of quarter wave plates permit examination of circularly polarized light. Birefringence measurements have been made with phase-modulated systems for examining the transient flow behavior of fluids.[9][10]

Birefringence of lipid bilayers can be measured using dual polarisation interferometry. This provides a measure of the degree of order within these fluid layers and how this order is disrupted when the layer interacts with other biomolecules.

Applications

Reflective twisted nematic liquid crystal display. Light reflected by surface (6) (or coming from a backlight) is horizontally polarized (5) and passes through the liquid crystal modulator (3) sandwiched in between transparent layers (2,4) containing electrodes. Horizontally polarized light is blocked by the vertically oriented polarizer (1) except where its polarization has been rotated by the liquid crystal (3), appearing bright to the viewer

Birefringence is used in many optical devices. Liquid crystal displays, the most common sort of flat panel display, cause their pixels to become lighter or darker through rotation of the polarization (circular birefringence) of linearly polarized light as viewed through a sheet polarizer at the screen's surface. Similarly, light modulators modulate the intensity of light through electrically induced birefringence of polarized light followed by a polarizer. The Lyot filter is a specialized narrowband spectral filter employing the wavelength dependence of birefringence. Wave plates are thin birefringent sheets widely used in certain optical equipment for modifying the polarization state of light passing through it.

Birefringence also plays an important role in second harmonic generation and other nonlinear optical components, as the crystals used for this purpose are almost always birefringent. By adjusting the angle of incidence, the effective refractive index of the extraordinary ray can be tuned in order to achieve phase matching which is required for efficient operation of these devices.

Medicine

Birefringence is utilized in medical diagnostics. One powerful accessory used with optical microscopes is a pair of crossed polarizing filters. Light from the source is polarized in the X direction after passing through the first polarizer, but above the specimen is a polarizer (a so-called analyzer) oriented in the Y direction. Therefore, no light from the source will be accepted by the analyzer, and the field will appear dark. However areas of the sample possessing birefringence will generally couple some of the X polarized light into the Y polarization; these areas will then appear bright against the dark background. Modifications to this basic principle can differentiate between positive and negative birefringence.

Urate crystals, with the crystals with their long axis seen as horizontal in this view being parallel to that of a red compensator filter. These appear as yellow, and are thereby of negative birefringence.

For instance, needle aspiration of fluid from a gouty joint will reveal negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals. Calcium pyrophosphate crystals, in contrast, show weak positive birefringence.[11] Urate crystals appear yellow and calcium pyrophosphate crystals appear blue when their long axes are aligned parallel to that of a red compensator filter,[12] or a crystal of known birefringence is added to the sample for comparison.

Birefringence can be observed in amyloid plaques such as are found in the brains of Alzheimer's patients when stained with a dye such as Congo Red. Modified proteins such as immunoglobulin light chains abnormally accumulate between cells, forming fibrils. Multiple folds of these fibers line up and take on a beta-pleated sheet conformation. Congo red dye intercalates between the folds and, when observed under polarized light, causes birefringence.

In ophthalmology, binocular retinal birefringence screening of the Henle fibers (photoreceptor axons that go radially outward from the fovea) provides a reliable detection of strabismus and possibly also of anisometropic amblyopia.[13] Furthermore, scanning laser polarimetry utilises the birefringence of the optic nerve fibre layer to indirectly quantify its thickness, which is of use in the assessment and monitoring of glaucoma.

Birefringence characteristics in sperm heads allow for the selection of spermatozoa for intracytoplasmic sperm injection.[14] Likewise, zona imaging uses birefringence on oocytes to select the ones with highest chances of successful pregnancy.[15] Birefringence of particles biopsied from pulmonary nodules indicates silicosis.

Stress induced birefringence

Color pattern of a plastic box with "frozen in" mechanical stress placed between two crossed polarizers.

Isotropic solids do not exhibit birefringence. However, when they are under mechanical stress, birefringence results. The stress can be applied externally or is "frozen in" after a birefringent plastic ware is cooled after it is manufactured using injection molding. When such a sample is placed between two crossed polarizers, colour patterns can be observed, because polarization of a light ray is rotated after passing through a birefingent material and the amount of rotation is dependent on wavelength. The experimental method called photoelasticity used for analyzing stress distribution in solids is based on the same principle.

Other cases of birefringence

Birefringence is observed in anisotropic elastic materials. In these materials, the two polarizations split according to their effective refractive indices which are also sensitive to stress.

The study of birefringence in shear waves traveling through the solid earth (the earth's liquid core does not support shear waves) is widely used in seismology.

Birefringence is widely used in mineralogy to identify rocks, minerals, and gemstones.

Birefringent rutile observed in different polarizations using a rotating polarizer (or

analyzer)

Theory

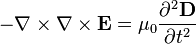

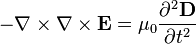

Birefringence results when a material's permittivity is not describable using a scalar value, but requires a tensor to relate the electric displacement (D) with the electric field (E). Consider a plane wave propagating in an anisotropic medium, with a permittivity tensor ε and assuming no magnetic permeability in the medium: . We shall assume that the electric field of a wave of angular frequency ω can be written in the form:

(2)

where r is the position vector, t is time, and E0 is a vector describing the electric field at r=0, t=0. Then we shall find the possible wave vectors k using Maxwell's equations from which we obtain:

(3a)

(3a)

(3b)

where the so-called electric displacement vector is now related to the electric field through the permittivity tensor ε:

Substituting the definition of and eqn. 2 into eqns. 3a-b leads to the conditions:

(4a)

(4b)

Eqn. 4b indicates that is orthogonal to the direction of the wavevector k, even though that is no longer generally true for as would be the case in an isotropic medium. Note that 4b follows from 4a; this is a consequence of our using the plane wave ansatz.

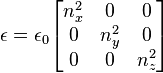

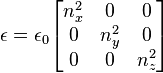

To find the allowed values of k for a given ω, E0 can be eliminated from eq 4a. If eqn 4a is written in Cartesian coordinates with the x, y and z axes chosen in the principal directions of the permitivity tensor ε, then

(4c)

(4c)

where the diagonal values are squares of the refractive indices for polarizations along the three principal axes x, y and z. With ε in this form, and noting that the speed of light , eqn. 4a becomes

(5a)

(5b)

(5c)

where Ex, Ey, Ez, kx, ky and kz are the components of E0 and k. This is a set of linear equations in Ex, Ey, Ez, and they have a non-trivial solution if the following determinant is zero:

(6)

(6)

Evaluating the determinant of eqn (6), and rearranging the terms, we obtain

-

In the case of a uniaxial material, choosing the optic axis to be in the z direction so that nx=ny=no and nz=ne, this expression can be factored into

(8)

Setting either of the factors in equation (8) to zero will define an ellipsoidal surface in the space of wave vectors k that are allowed for a given ω. The first factor being zero defines a sphere corresponding to ordinary rays, in which the effective refractive index is exactly no. The second defines a spheroid symmetric about the z axis. This solution corresponds to extraordinary rays in which the effective refractive index is in between no and ne. Therefore, for any arbitrary direction of propagation, two distinct wavevectors k are allowed corresponding to the polarizations of the ordinary and extraordinary rays. A general state of polarization launched into the medium can be decomposed into two such waves which will then propagate with different k vectors (except in the case of propagation in the direction of the optic axis).

For a biaxial material a similar but more complicated condition on the two waves can be described.[16] What can be seen from the equation is the following: for a given k, there are two positive values of ω that solve the above quartic equation (8). The values ωi, i=1,2, correspond to two perpendicular linear polarizations Di, i = 1,2 of the displacement vector in the 2-plane k⊥. Alternately put, since the dispersion relation is linear, for a fixed frequency ω and direction of motion k/|k|, there are there are two admissible wavenumbers ki and effective refractive indices ni=ni (k/|k|) corresponding to the polarization directions Di, i = 1,2. If n1 = n2, then the effective refractive index is independent of the direction of polarization, and there is consequently no visible birefringence if light is shined in this direction. Such a direction k defines an axis through the crystal.[clarification needed] In the case of generic, distinct principal refractive indices, nx, ny, nz, further analysis shows that there are exactly two axes, which led historically to the "bi" in "biaxial".

See also

- Cotton-Mouton effect

- Crystal optics

- Dichroism

- John Kerr

- Periodic poling

References

- ^ "Olympus Microscopy Resource Center". Olympus America Inc. Retrieved 2011-11-13.

- ^ See:

- Erasmus Bartholin, Experimenta crystalli islandici disdiaclastici quibus mira & infolita refractio detegitur [Experiments on birefringent Icelandic crystal through which is detected a remarkable and unique refraction] (Copenhagen, Denmark: Daniel Paulli, 1669).

- Erasmus Bartholin (January 1, 1670) "An account of sundry experiments made and communicated by that learn'd mathematician, Dr. Erasmus Bartholin, upon a chrystal-like body, sent to him out of Island," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 5 : 2041-2048.

- ^ Landau, L. D., and Lifshitz, E. M., Electrodynamics of Continuous Media, Vol. 8 of the Course of Theoretical Physics 1960 (Pergamon Press), §79

- ^ Brad Amos. Birefringence for facetors I : what is birefringence? First published in StoneChat, the Journal of the UK Facet Cutter's Guild. January–March. edition 2005

- ^ a b c Elert, Glenn. "Refraction". The Physics Hypertextbook.

- ^ The Use of Birefringence for Predicting the Stiffness of Injection Molded Polycarbonate Discs

- ^ M. Wolman, F.H. Kasten, "Polarized light microscopy in the study of the molecular structure of collagen and reticulin," Histochemistry (1986), 85:41-49

- ^ Sano, Y. "Optical anistropy of bovine serum albumin," J. Colliod Int. Sci., 124: 403-407 (1988)

- ^ Frattini, P., Fuller, G., "A note on phase-modulated flow birefringence: a promising rheo-optical method,' J. Rheol., 28: 61 (1984)

- ^ Doyle, P., Shaqfeh, E.S.G., Spiegelberg, S.H., McKinley, G.H., "Relaxation of dilute polymer solutions following extensional flow," J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., 86:79-110 (1998).

- ^ Hardy RH, Nation B (June 1984). "Acute gout and the accident and emergency department". Arch Emerg Med 1 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1136/emj.1.2.89. PMC 1285204. PMID 6536274.

- ^ The Approach to the Painful Joint Workup Author: Alan N Baer; Chief Editor: Herbert S Diamond. Updated: Nov 22, 2010

- ^ Reed M. Jost; Joost Felius; Eileen E. Birch (August 2014). "High sensitivity of binocular retinal birefringence screening for anisometropic amblyopia without strabismus". Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (JAAPOS) 18 (4): e5–e6.

- ^ Gianaroli L, Magli MC, Ferraretti AP; et al. (December 2008). "Birefringence characteristics in sperm heads allow for the selection of reacted spermatozoa for intracytoplasmic sperm injection". Fertil. Steril. 93 (3): 807–13. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.024. PMID 19064263.

- ^ Ebner T, Balaban B, Moser M; et al. (May 2009). "Automatic user-independent zona pellucida imaging at the oocyte stage allows for the prediction of preimplantation development". Fertil. Steril. 94 (3): 913–920. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.106. PMID 19439291.

- ^ Born M, and Wolf E, Principles of Optics, 7th Ed. 1999 (Cambridge University Press), §15.3.3

External links

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Birefringence. |

- Stress Analysis Apparatus (based on Birefringence theory)

- http://www.olympusmicro.com/primer/lightandcolor/birefringence.html

- Video of stress birefringence in Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA or Plexiglas).

- Artist Austine Wood Comarow employs birefringence to create kinetic figurative images.

- Merrifield, Michael. "Birefringence". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- The Birefringence of Thin Ice (Tom Wagner, photographer)

(3a)

(3a) (4c)

(4c) (6)

(6)